Liubo

Liubo is one of the most mysterious game of the whole Human history. Liubo is a ancient Chinese board-game whose rules are forgotten. However, since three decades, several studies have been done, backed by several archaeological findings. Most of the information given here are drawn from Hermann Josef Röllicke's paper (Von « Winkelwegen », « Eulen » und « Fischziehern » - liubo : ein altenchinesisches Brettspiel für Geister und Menschen) published in Board Game Studies n°2, 1999. Also, I should thank here Thierry Depaulis who informed me of his personal understanding related to this game. However, what is expressed reflects my view only and can not be attributed to other authors.

The name Liubo comes from Chinese (liu = six, bo = sticks). This game was played in ancient China, at least since the Zhanguo (The Warring States) era (4th c. BC) and maybe much earlier (7th c. BC) as it is evoked in Confucius' Analects (Book XVII, 22): "It is difficult for a man who always has a full stomach to put his mind to some use. Are there not players of liubo and weiqi? Even playing these games is better than being idle."

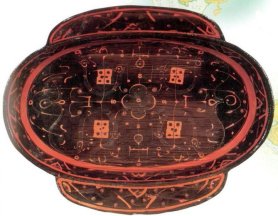

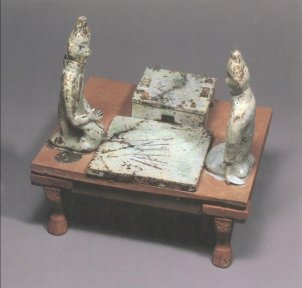

Puddingstone

footed Liubo Board (41.5x41.5 cm) inlaid with bone with four ivory

Liubo pieces.

Han dynasty, 206 BC - AD 220.

From E&J

Frankel gallery, New York

Apparently very popular during the Han dynasties (207 BC - 220 AD) when the best players were well respected and formed a corporation, it later vanished, probably outshone by the Chinese adaptation of Nard (a Backgammon ancestor) coming from India and Persia when the Tang (618-907) re-opened the Silk Road. The very last reference dates from the Song time (before 1162) where it was quoted as an “old game”. Archaeological findings are not scarce and there are quite a few literary evocations, nevertheless, nobody knows what the rules of the game were.

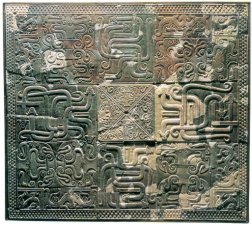

Liubo

board and its drawing showing the classical “TLV” pattern as

found in Zhongshan, 4th c. BC.

(Photo from Maurizio

Scarpari,"Chine ancienne", Gründ, Paris, 2000)

Especially intriguing is the board whose pattern is found in other artefacts like the famous “TLV” bronze mirrors from the Han dynasty. Its cultural connection is almost explained and understood, but it still resists in delivering any clue on how it could have been used for playing!

|

|

|

|

|

|

Some TLV bronze mirrors

The

round mirror has a round knob, which is surrounded by nine smaller

knobs. Four characters - "chang yi zi sun (to benefit future

generations forever)" - are inscribed respectively inside the

four squares framed with double-line wave patterns at the four

corners. The inscriptions on the outer edge include some squares,

with main decorative patterns being regular ones, which surround

the azure dragon, white tiger, vermilion bird, black tortoise,

auspicious animals etc. The mirror is also decorated with patterns

of the variations of "the four divine creatures" and has

shiny rust scales like those on an ancient coin.

That pattern bears a lot of symmetry. Similar forms can be found in rather surprising artefact. Take a look at this very elegant cup from the Warring States era (475 - 221 BC). Isn't pattern familiar?

A

splendid "cup with ears"

(Photo from Maurizio

Scarpari,"Chine ancienne", Gründ, Paris, 2000)

The board and its pattern carried a strong astronomical content. Compare with a Chinese compass.

Ancient

Chinese Compass

Many theories have been advanced to explain what kind of game Liubo was. Murray did not cite that name but seemed to evoke it with a “Luk tsut k’i (or Liuziqi in Pinyin, six men game)” which he presented as an alignment game much like Merels. For some authors, Liubo may have given birth to Xiangqi, Chinese Chess. This presentation is sometimes made on Internet sites presenting the history of Xiangqi. It might be exaggerated, however, some influence of Liubo on Xiangqi should not be discarded too quickly (marking of the board, presence of a river, presence of a King and 5 Pawns, …).

Today, most authors (Lhôte, Parlett, Li,...) and specialists believe that Liubo was probably a chance game, a sort of race game with captures.

The board was independently used for divination. This is not surprising as this happened also for many other race games in other civilizations. Maybe the Liubo board had been inspired by those tortoise shells that ancient Chinese put on a fire to see what cracks would appear on the obverse side. By interpreting the cracks the soothsayer predicted the outcome of an event. The tortoise shell looks like a rectangle with corners cut and the cracks are like segmented lines. Is there a link ?

A wooden slip has been excavated in a tomb at Yinwan in 1993 presenting a Liubo-like diagram along with a chart of characters addressing several oracles. A full explanation of the divining process has been recently proposed (ZENG Lanying (Lillian L. TSENG), « Divining from the Game Liubo : An Explanation of A Han Wooden Slip », China Archaelogy and Art Digest, « Fortune, Games and Gaming », Vol.4, n°4, October-December 1999). Although nothing proves that the moving sequence was identical for both the game and the divination, this work brings some light on the allowed positions and the path between them.

Diagram

found on a wooden slip at Yinwan (from Zeng Lanying)

Reconstruction

diagram proposed by Zeng Lanying where the 60 days of the Ancient

Chinese hexadecimal cycle can be located for divination purpose

The game material also comprised two sets of stones (qi) – 6 white and 6 black – made from ivory, bone, bronze or jade, and 6 split bamboo sticks presenting a flat and a bombed faces.

It is clear that the players did not simply throw the sticks, but they rather placed them in order to interpret them. Then, the results was comparable to the famous hexagrams, related to the Tao philosophy, and the Yijing, the Book of Changes. Made of six continuous or dotted lines, representing the yang and the yin principles respectively, they were the key of the Chinese astrology.

A

set of liubo tools for entertainment was unearthed from Tomb No. 3

at the Mawangdui Site. The set is composed of a board, 12 big

chess pieces (six black ones and six white ones), 20 small chess

pieces, 42 chips and a dice, all of which are in a special lacquer

box. These tools are especially designed for liubo games.

Bamboo

sticks for the yijing

From Royal

Ontario Museum.

Sometimes, the material includes one or two complex 18 sided-dice as an alternative to the bamboo rods.

18-sided

Chinese dice, unearthed from Tomb no.

3 at Mawangdui, Western Han dynasty

From Royal

Ontario Museum

18-sided

dice, China, Han dynasty (206 BC - 220 AD).

Top: bronze inlaid

with gold, silver, turquoise, agate and rock crystal, diameter 3.5

cm.

Bottom: lacquered wood: diameter 5.1 cm

(from Asian

Games The Art of Contest, Asia Society, 2004)

Liubo

dice?

The illustrations often show an auxiliary surface, the boxi, where the players could arrange the sticks to interpret them.

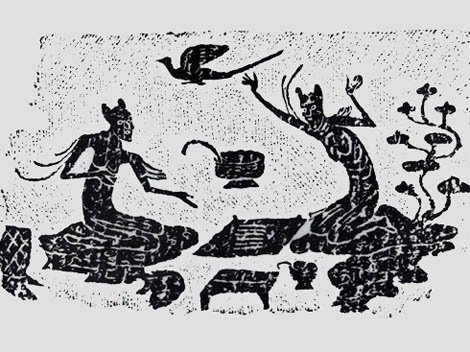

The Liubo appears to have borne a strong mystical spirit and its board was at the same time a cosmological, a calendar and a divination instrument.

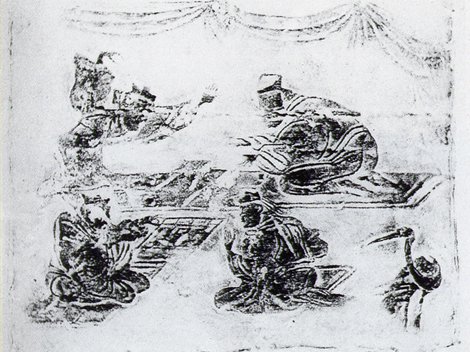

Two

"immortals" playing Liubo. Relief on mortuar brick.

Han

Pictorial brick. The picture is partially damaged. There are two

winged immortals sitting in a half-kneeling position, playing

liubo. Another winged immortal at the left bottom is holding the

rein of a divine horse with both hands. The horse, raising its

head and neighing, looks as if it's about to gallop. A crane is

behind the horse and a winged immortal is standing in front of it

with something in his hands.

Liubo

players. Eastern Han dynasty, 1st-2nd century AD

The figures in

this group are gambling. They are playing Liubo, a game thought to

be popular among both mortals and immortals. The board is marked

with divination symbols, and the game pieces show the animals of

the four directions: the White Tiger (West), the Green Dragon

(East), the Vermilion Bird (South) and the Tortoise, with a snake

coiled around its body, known as the Dark Warrior (North). The

models are made of earthenware, covered with a green lead glaze.

Lead glazes were used only for burial goods, because they are

poisonous. Height: 25.6 cm

From British

Museum, London.

Pottery

figurines playing Liubo. Han dynasty, 206 BC - 220 AD. Unearthed

at Lingbao, Henan. h=24 cm..

From Henan

Museum, Zhengzhou.

Looks

like the same artifact

Tomb

figures of two Liubo players, table and board, ceramic. Eastern

Han dynasty.

From Royal

Ontario Museum.

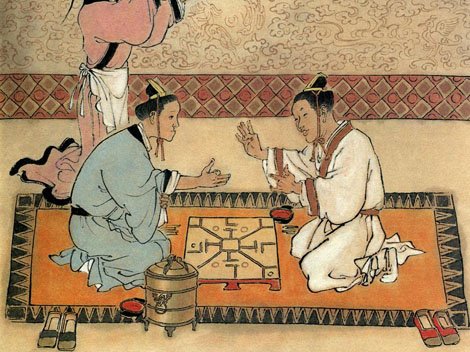

Three

Capped Men (Probably Two Players and One Observer) Kneeling around

a Low Table and Playing Liubo

China, Eastern Han period,

1st-2nd century

Lead-glazed ware: Molded, brick red earthenware

(the game board made separately from the table), with degraded,

opalescent, emerald green, lead-fl,

Each figure: 17.0 x 12.5 x

11.0 cm; Table: 5.5 x 26.5 x 23.5 cm;

Game board and affixed

pieces: 2.0 x 16.0 x 12.0 cm

From Collection of Anthony

M. Solomon, Photo by Maggie Nimkin, Harvard

University Art Museums

Liubo

game in process, Han dynasty. Red pottery. One can see the rods

scattered as thrown by the left player. On the board, one piece

seems bigger than the others. It could be the xiao

(leader, owl).

Liubo

players at play, Eastern Han dynasty

(Photo from Maurizio

Scarpari,"Chine ancienne", Gründ, Paris, 2000)

Set

of Liubo Game Figures 1st cent. BC - 1st cent. AD Chinese, Han

Dynasty

Photo by Katherine Wetzel © Virginia

Museum of Fine Arts

Set

of dice players, Western Han dynasty

(Photo from Maurizio

Scarpari,"Chine ancienne", Gründ, Paris, 2000)

Liubo board with four game figures, Western Han dynasty, 206 BC - 8 AC. Bronze. Museum of Autonomous Region Zhuang of Guangxi. From "Archéologie chinoise, trésor de la Région du Guangxi", Somogy, Paris, 2003

A very nice website on Liubo from which several

pictures have been borrowed. Many

thanks:

http://www.cultural-china.com/chinaWH/html/en/11Kaleidoscope2115.html